“Curiosity is one of the great secrets of happiness.”

—Bryant H. McGill

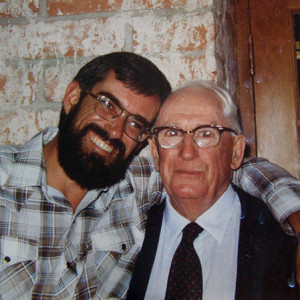

This story contributed by Peter H. Smith.

He was born in 1902 in Easley, South Carolina. No electricity, no radio, no television, no cars, no running water, and no stores — they grew food on the family farm. Outdoor kitchen and outdoor bathrooms. You get the picture.

But my dad, Hugh Smith, was a born adventurer.

A small farming town could only hold him so long. In 1923, at the age of 21, he drove his Ford Model T across the country, camping along the roadside. He just wanted to “see what’s out there.” Since childhood, he was consumed with an insatiable curiosity for the world and beyond.

His first real “adventure” was Rochester Med School. But he wasn’t satisfied with just the M.D. — he later attended Johns Hopkins for a second degree in Public Health.

Working as a virologist for the Rockefeller Foundation, he would take on his next (and probably his greatest) adventure… Yellow fever.

In the 1930’s, yellow fever was an epidemic in South America and Africa. Through Rockefeller, Dad was paired with colleague Max Theiler to find the cure. But no stuffy science lab was going to confine my dad. He demanded to be on the front lines — in Brazil, Colombia, and other affected countries.

A cure had been developed and tested with efficacy in Panama, but was far too expensive to be produced for widespread application.

Dad and Theiler headed up the team that developed the ultimate 17-D vaccine.

Between 1940 and 1947, Rockefeller produced 28 million doses of the vaccine, terminating yellow fever as a major infectious disease. Not only that, Dad was the first one to test the new vaccine … on himself! He was ill for about a week, then recovered slowly – much to the relief of his fellow scientists.

My mother sometimes grumbled that he should have received that Nobel Prize in ’51 instead of his “boss,” Theiler, because “he did all the work and even tested it on himself first!”

So, after curing yellow fever, Dad needed another great adventure. Through Rockefeller, he arranged to be stationed in London during World War II. Again, on the front lines. He told my younger brother and me stories about standing on the roof of his hotel, watching V2 rockets hail down from the sky onto the streets of London. Dad was there to “help however he could.”

After the war, he came back to Rockefeller headquarters in New York City to manage research for the foundation’s global efforts. He married my mom, who was his secretary at the time.

My dad had lived an amazingly full and rewarding life by the age of 52, so in 1954, he “retired” and moved to Tucson, Arizona with his young family. His “retirement” included a professorship at the University of Arizona, leading the local public health system, and heading up the Red Cross for a short stint. Not a very relaxed retirement, but as you know by now, my dad just wasn’t a “relaxed” kind of guy.

At nine years old, I remember him gathering us outside to watch the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1 fly overhead. “There it is! You see?!” he exclaimed. I will never forget the transfixed look in my dad’s eyes as his finger slowly traced it through the night sky… pure over-joyous wonder. He explained that the Soviets had gotten there first, but the United States would be soon to follow with the Explorer 1 satellite.

We were both captivated by the sight of a man-made “star” moving across the darkened sky. That night set me on my own trajectory for life. The competition with the Soviets fueled the Space Age for more than 30 years, and my career along with it.

Today, I am a Professor for the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona. My greatest adventure was landing on Mars in 2008 — our robotic spacecraft, Phoenix, that is.

My father passed away in ’95 — I so wish he could have seen that.

He was a man deeply fascinated by the world, and the universe beyond. A penchant for the pilgrimage. A doctor. A disease curer. And one heck of a great dad.

Right after Dad died I found this quote by Omar Khayyam on his desk:

The worldly hope men set their hearts upon

Turns ashes — or it prospers; and anon

Like snow upon the desert’s dusty face,

Lighting a little hour or two — is gone.

And one final thought:

The world is bewitching, and sometimes quite scary, but there is nothing more frightful than living a life of complacence.

Peter H. Smith

Peter H. Smith is a Professor Emeritus at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, where he holds the inaugural Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair in Integrative Science. With the landing of robotic spacecraft, Phoenix, on Mars in 2008, Smith has become a recognized pioneer in the field of space discovery.